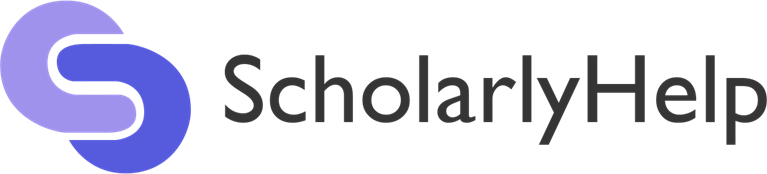

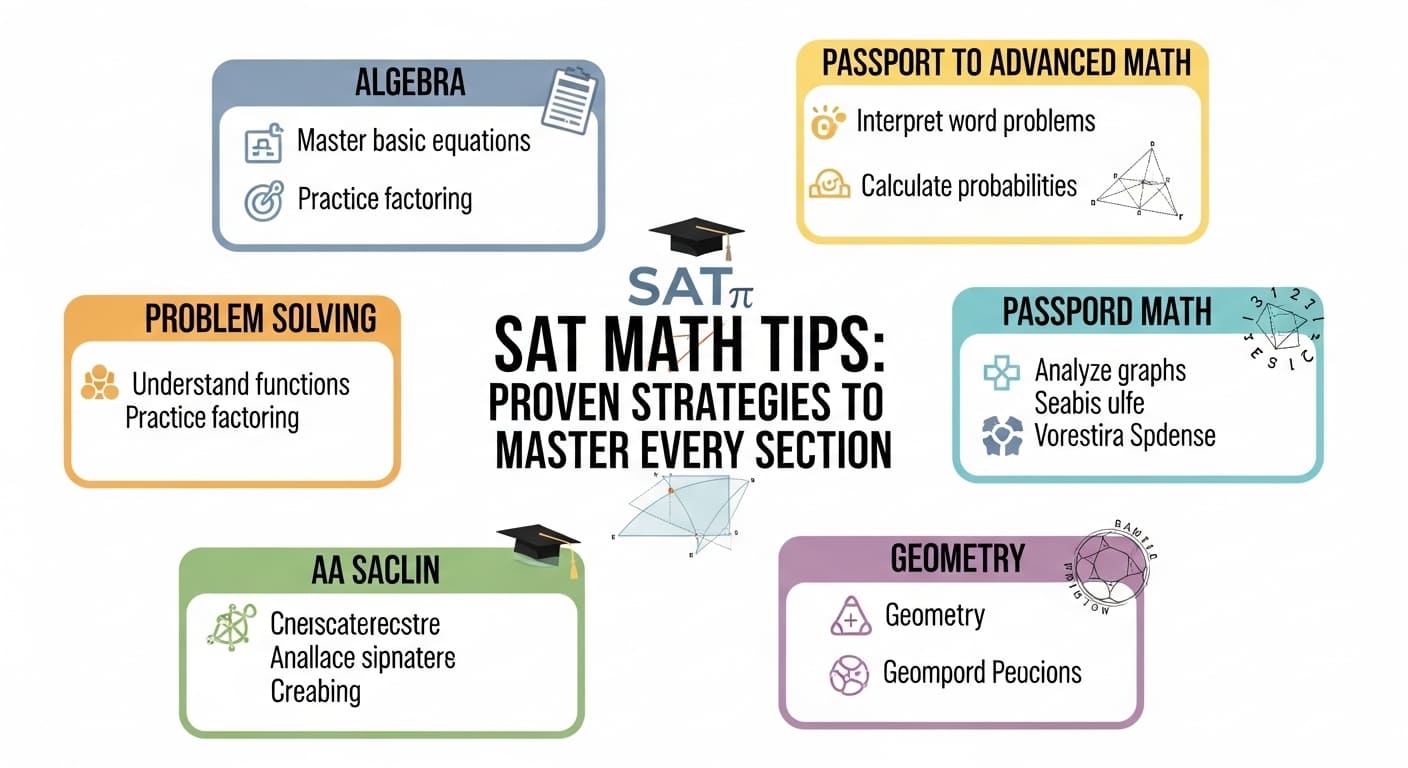

Key Concepts That Make or Break Understanding

Mastering organic chemistry requires clarity in a few foundational areas. Without them, every new topic feels confusing.

1. Structure and Bonding

Understanding hybridization, bond angles, and resonance gives you insight into molecular stability and reactivity. Learn how atoms arrange themselves to minimize energy — it’s the foundation of predicting chemical behavior.

2. Functional Groups

Recognizing functional groups (alcohols, ketones, acids, etc.) helps categorize molecules and anticipate their reactions. Each functional group behaves predictably under certain conditions.

3. Reaction Mechanisms

Mechanisms explain how and why reactions occur. Mastering curved-arrow notation (electron flow) is crucial for solving reaction-based questions logically.

4. Stereochemistry

Visualizing molecules in 3D and understanding chirality, enantiomers, and diastereomers are essential for understanding biochemical reactions and pharmaceuticals.

5. Acid-Base Chemistry

Acidity and basicity determine reactivity in many organic reactions. Reviewing general chemistry principles helps you see why some compounds donate or accept protons more readily.

6. Resonance and Stability

Resonance delocalizes electrons, stabilizing molecules. Recognizing possible resonance structures improves your predictions of reactivity and product outcomes.

How to Master Organic Chemistry

Success in organic chemistry depends less on innate talent and more on study strategy and consistent practice.

Effective Study Strategies to Excel

-

Learn Mechanisms, Not Reactions:

Instead of memorizing product lists, learn the underlying electron movements. This helps you deduce outcomes in unfamiliar problems.

-

Use Molecular Models:

Model kits or 3D apps help visualize bonds and molecular geometry, making abstract structures tangible.

-

Draw Constantly:

Rewriting mechanisms improves muscle memory and reinforces logic. Sketch every step, electrons, intermediates, and products.

-

Practice spaced repetition:

Review earlier concepts frequently using flashcards or digital tools. Organic chemistry builds cumulatively; spaced repetition prevents forgetting.

-

Solve Reaction Problems Daily:

Consistency is key. Try problems that force you to predict mechanisms, not just recall them.

-

Focus on Patterns:

Look for repeating patterns in reactions, nucleophilic attacks, electrophilic substitutions, elimination pathways, etc. Recognizing these patterns reduces overwhelm.

Mindset Shifts for Success

Organic chemistry isn’t about perfection; it’s about progress. Approach each topic with curiosity rather than fear. Remember, even top chemists struggled initially.

Key mindset tips:

- Embrace mistakes as learning tools.

- Break large reactions into manageable steps.

- Connect concepts to real-life chemistry (medicine, food, environment).

- Stay patient, understanding compounds takes time and practice.

Common Mistakes Students Make in Organic Chemistry

Many students fall into avoidable traps that make learning more difficult. Recognizing these mistakes early can drastically improve comprehension.

Six Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Memorizing Without Understanding: Memorization may work short term but fails in complex problem-solving.

- Ignoring Mechanisms: Skipping steps makes it impossible to explain why a reaction works.

- Not Reviewing Fundamentals: Forgetting acid-base chemistry or hybridization weakens advanced understanding.

- Studying Passively: Simply reading notes doesn’t build problem-solving skills; active drawing and solving do.

- Cramming Before Exams: Organic chemistry demands continuous engagement, not last-minute study sessions.

- Overlooking Visual Learning: Avoiding molecular models limits understanding of 3D stereochemistry.

How to Simplify Complex Topics

When you face an overwhelming concept, break it into steps:

- Identify what’s known (reactants, reagents).

- Determine which atom is electrophilic and which is nucleophilic.

- Track electron flow step by step.

- Check the resonance and stability of intermediates.

- Confirm products logically based on mechanism patterns.

Using this method turns intimidating reactions into solvable puzzles.

How Organic Chemistry Connects to Real-World Applications

Organic chemistry is foundational to modern science and everyday life. From developing pharmaceuticals to designing new polymers and fuels, it underpins countless innovations.

A deeper understanding of organic reactions allows chemists to:

- Design sustainable materials

- Create safer drugs and fertilizers

- Develop green chemistry solutions for pollution control

- Innovate in energy, agriculture, and environmental protection

Even computational chemistry concepts like signed integers in chemistry play a role in data modeling and quantum chemistry analysis.

Pain Points Students Commonly Face

Students often struggle with the volume of content, rote memorization, and mechanism visualization. Many also experience anxiety before exams due to cumulative topic buildup.

To overcome these:

- Develop weekly study plans focused on mechanism mastery.

- Join peer study groups for discussion.

- Use color-coded reaction maps for better memory retention.

- Prioritize conceptual clarity over rote memorization.

Conclusion

Organic chemistry is hard because it requires analytical reasoning, visualization, and conceptual thinking, not just memorization. However, once you understand the principles that drive reactivity and mechanisms, the subject transforms from intimidating to logical and even elegant.

By using structured study methods, focusing on mechanisms, and connecting chemistry to real-world relevance, you can not only survive but truly master organic chemistry. Remember, the challenge itself is what makes the mastery so rewarding.